From Rainbows

It is regularly said that you can’t overdose on psychedelics: “the only danger is if you take too little,” McKenna liked to say. While this is probably technically true—cardiac arrest is unlikely—I remain undecided on this point.

But for the moment I’ll imagine that, given the right set and setting, this medicine flows through your psyche as rain flows through a forest, leaving behind a glimmering jungle. The long glowing afterburn of these experiences is what remains incredible to me, the exact opposite of a hangover; whereas whiskey or MDMA steals energy from tomorrow, the psychedelic can add energy to your tomorrows many months in advance: new color, new sound, awakening to the more-than-human world, the whole world becoming rather more alive and far more strange than you had previously imagined.

Or at least that’s what happened to me: a journey from a dead and mechanical nature, to an all-too vivid world of spirit, as if my own mind had spilled into a greater mind that had always been there this whole time. Had there been a rift between myself and, for example, the forest as a living minded entity, the mushroom filled this rift with lightning. In short the forest became sacred. Make no mistake about it, this is a religious position that I’ve somehow dosed myself into. I believe in the forest. What is yet more remarkable is that this was my intent; the set in my setting: I wanted a forest conversion experience and the mushroom made it happen.

The other curious feature of psychedelic topography is that ground becomes insubstantial; were we to propose a kind of psychedelic materialism: the first principle of which would be that material, the literal ground, is not really there, can vanish in an instant, turn at once into an abyss of rainbows. Even a scientist will admit that colors are not real; and yet here one passes through a vortex where color becomes the basic reality One does not overdose because one merely falls away into neon impossibilities; the very structure of reality, that one had been so dependent on, that had been so real, phase shifts into uncanny refractions of impossible geometries, chromatic beatitude, flows of affect, and together with the curious new presence of entities, whether organic—insect, plant or bird—or otherworldly, the discarnate, pure spirit, neither material, nor ideal (for all I know anyways); is that spirit a part of me? Yes? No? Maybe? The real resides beyond the limit; but what is real has no limit. One realizes that the ground is always already uncanny; not entirely there. Where one runs out of ground one imagines it.

I am always struck by the child’s ability to recognize spirit. It can seem at times as if the child lives in a world alive with sprites, if not, in fact the actual spirit world; made of half raw imagination and half visionary states of perception. Like William Blake’s four-fold vision—who himself saw a tree of angels when he was a child—it’s the kind of imaginal power that creates the world as it is perceived. The world is created, is made up, by the child, even as it appears to them. Either this or what we call imagination is a kind of radical perception without limits, where the doors of perception had not yet been set on the hinges, where there is not even a wall to put a door in yet. Just as one may travel into a realm of unthinkable rainbows with the aid of plant-medicines, so the child proceeds from out of those same rainbows, beamed from way down in the uterine dark—in the black universe, where void is the plenum and black is the fount of all color.

The aesthetic link between childhood entertainment and psychedelia is no accident. Could not all the bright colors and basic shapes of childhood be an inverted endopsychic perception of the impossible rainbow void that is the intrauterine environment? An alphabet realm, where the first alphabet is a rainbow written in the day-glo tryptamine-style of the beyond; so much so that any child may as well have been delivered straight from the land of the fay…

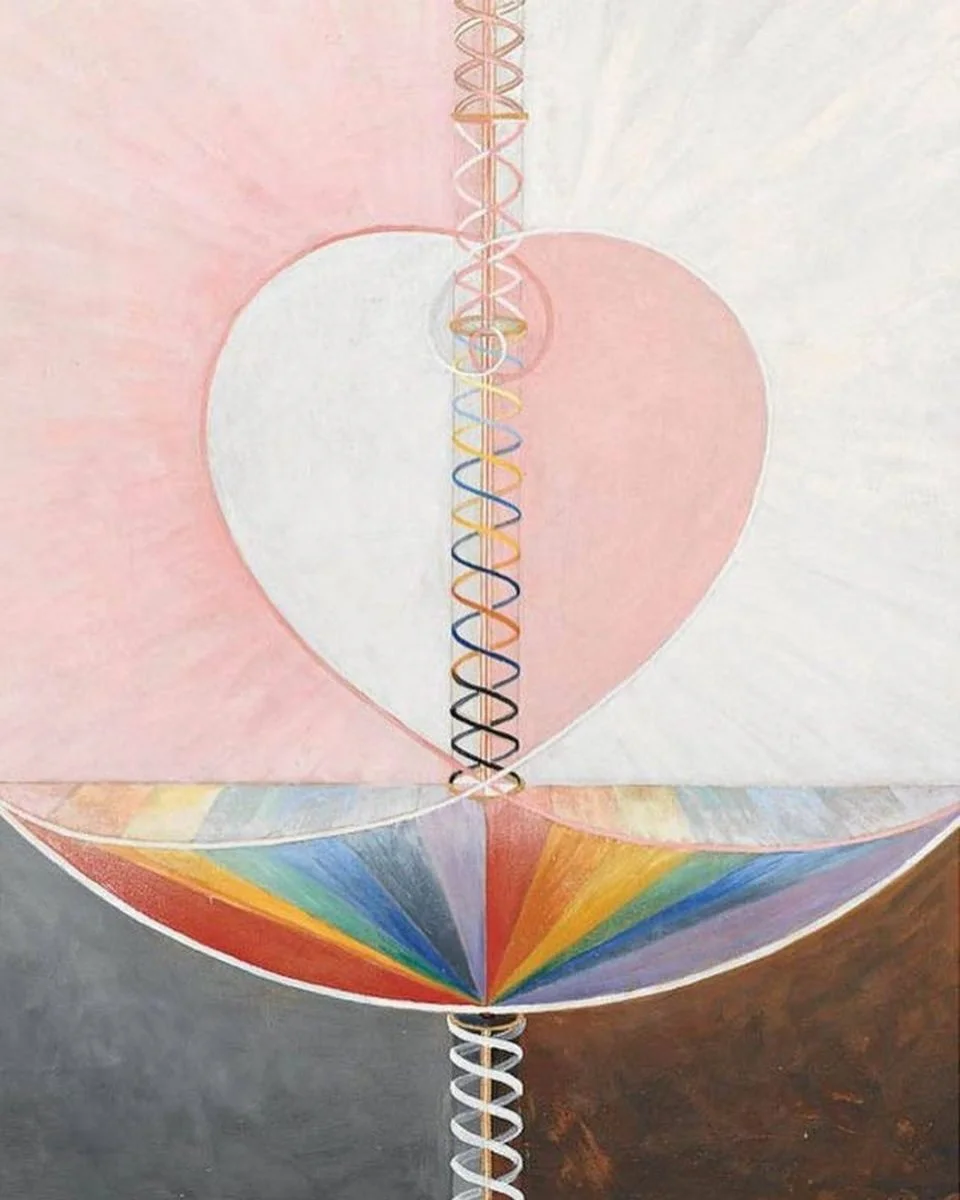

The Dove no. 14, 1915, Hilma af Klint

The Dove no. 1, 1915, Hilma af Klint