Death by Astonishment (2025)

It has been said that were aliens to arrive on planet earth tomorrow, no one would believe it. That seems about right because as it turns out, science has discovered alien intelligence. And no one cares. While these fay entities have been known from time immemorial from the amazon to Ireland, modernity only discovered this preposterous alien world, basically yesterday, by (among others) William S. Burroughs—very few believed him either. “I would like to sound a word of urgent warning,” he wrote to Timothy Leary of the nightmare drug N,N-dimethyltryptamine; a drug from hell by which he had been trapped in a white-hot lattice oven, regarded by pitiless insectoid eyes. Burroughs, maybe, had a bad conscience, because Leary then promptly dosed Ram Dass (then Richard Alpert) and he fell into a beatific state of serenity that “lasted for a million years.” Go figure.

Since then science has confirmed similar reports time and again. When smoked or taken intravenously, the DMT user is whisked away to a higher-dimensional non-euclidian world populated by an array of non-human entities such as elves, fairies, dragons or giant insects, the very stuff of children’s stories. That the existence of an independent alien world, more real than real, has been verified in the lab, repeatedly, by now countless test subjects, is one of those incredible facts too weird to be true; it tends to make people’s eyes glaze over. Elves? Really? But one only has to smoke DMT to go there.

The skeptics will say that this is just drug-addled psychobabble and they are right. But they are forgetting that their whole brain is made out of cascading sheets of psychobabble; that it’s all psychobabble all the way down, from dreams to daylight to dying—in fact there is very little in human experience that is not drug-addled and once we accept that we are determined in the last instance by molecules, then we might begin to ask: what exactly is this molecule in particular? An endogenous molecule produced in the body—and nearly ubiquitous in nature—that, when smoked or ingested, allows immediate access to the most incognito of terra incognitas—as if it were a wormhole to Betelgeuse.

Death by Astonishment, by Andrew R. Gallimore, is his most recent attempt to examine this question: what he deems the scientific question of the era—and to which he levies all of the bristling technology and psychobabble of neuroscience to form an answer. His basic thesis, according to his theory of the mind, is that the DMT experience resides on another order of brain state than that of dream, hallucination, or even our knitting together of the phenomenal world. From the neurological perspective it is as if the tryptamine molecule key, set into its neurochemical tumbler, becomes an antenna that receives an entire coherent world of information that arrives from elsewhere and exists outside of the users mental stock of representations by which their waking-life is produced. In this sense it truly is alien; the far antipode of psyche. Unlike the dream produced from the day’s residues, DMT space is an ex-nihillo world, erupting into consciousness with all of the culture shock of a trip to the far side of hell; you are not in people-land anymore.

Gallimore regards the tryptamine as a technology, and in previous books has concocted what he calls a game, but that reads, to me anyhow, as a technological drug-based religion, the goal of which is to make an “irreversible passage” into the higher-dimensional reality of DMT space. Hmm…sound familiar? I’ve been to DMT space and made contact with the natives there, and while this visit made waking reality pale and dingy by comparison, I did not have any strong desire to stay there—just FYI.

Gallimore makes repeated insistence that the residents of DMT space are super-intelligent and even possess “wisdom” but he is not forthright in what this wisdom is. This is because communication between elfkind and humankind is a bit sketchy: I’m not sure they speak English down there. Nevertheless, communication of a kind, does happen. Terence McKenna’s DMT gospel message, that he received from probably one too many trips to elf-land, is that one must co-produce one’s reality through language; which sounds a bit psychoanalytic to me, but then I’m biased. But the meaning is loud and clear: subjective reality, in as much as it is made out of fantasy, is fungible; to change one’s reality one must only swap one fantasy for another. Fantasy is manipulated by language, by glossolalia, by singing. This is what the psychoanalyst means when they speak of the magic of words.

McKenna, who coined the term death by astonishment, had what can only be a radical conversion experience when he first encountered DMT: everything he thought he knew, all of his philosophy, science and politics, was invalidated in an instant upon his exit from hyperspace. This is typical of the DMT experience: it tends to be reality shredding. And yet here you are afterwards set back down in Kansas. Kansas is still “there” so to speak, but it is now a whole hell of a lot weirder; the hard ground of Kansas is not entirely ground anymore.

Gallimore’s book, despite its subtitle “Confronting the Mystery of the World's Strangest Drug,” tends to strip the weirdness out of this weirdest of molecules. Chock this up as an effect of Occam’s razor, where the mystery is systematically cut away by science and replaced by… a technology fetish. Gallimore lofts the rather lame speculation that these higher-dimensional elves have progressed so far in the development of technology that they have achieved the singularity: in short, they are the result of superintelligent recursive AI. This is a classic example of the unitary illusion where what is known becomes all that can be known. “If the Ox could paint, his god would look like an Ox” as Xenophanes once said. That Gallimore’s best guess is that this impossible hyperspace is the result of advanced technology is about as square as it gets. A squareness that is compounded by his recourse to clunky Jungian archetypes—I mean, seriously?

It is also readily apparent, to me, that one does not need neuroscience to determine that the DMT experience is on a different order of magnitude to that of a dream or waking life. This is in part what is so ontology-shredding about it. One never knew that there were colors that vivid; let alone discarnate entities, dancing around, overjoyed to see you, made entirely out of those colors. Still one can’t blame Gallimore for becoming religious, for this is the very stuff that religion is made out of. And in that regard it would seem that various global mythologies have a great deal more to say about the other world, than does the scientist.

Tibetan Buddhism, for example, with its mandalas, its jewels and bright colors, its all pervading darkness, looks, from this angle, as if it were a religion based on DMT. Does not The Tibetan Book of the Dead, with its descriptions of an intermediate realm full of luminous and wrathful entities, appear to be what amounts to a veritable Lonely Planet guide to DMT space?

And likewise, from indigenous Amazonia, would not the cosmic serpent mythology, that is itself derived from DMT via Ayahuasca, seem to indicate that DMT space is somehow inside of DNA…?

The prophet Ezekiel’s famous encounter with a fiery chariot reads to many today as a DMT vision. This blazing chariot with its strange beings, its eyed wheels within wheels and racing molten lights would go on to found an entire jewish mystical tradition, known as the Merkabah (chariot), lasting for a thousand years and forming the basis of what we now know as Kabbalah.

Such speculations are highly incredulous. And yet it would seem, viewed from the DMT standpoint, that our situation does not really support much credulity; as McKenna liked to remind us, reality is not weirder than we suppose, it is far weirder than we can suppose. While the astonishment of DMT produces endless conjecture, no one conjecture is adequate to the astonishment. This is similar to Laruelle’s notion of Unilateral Duality: while the One gives rise to an endless series of philosophy, no one philosophy is adequate to the One.

Furthermore, should your own philosophy get shredded, you can count your self lucky; you’ve arrived at the rare and privileged position of beginner’s mind. It’s good to not know anything once in a while—or always.

This is not to say that science has nothing to say in these matters but rather that it is, as usual, late to the party.

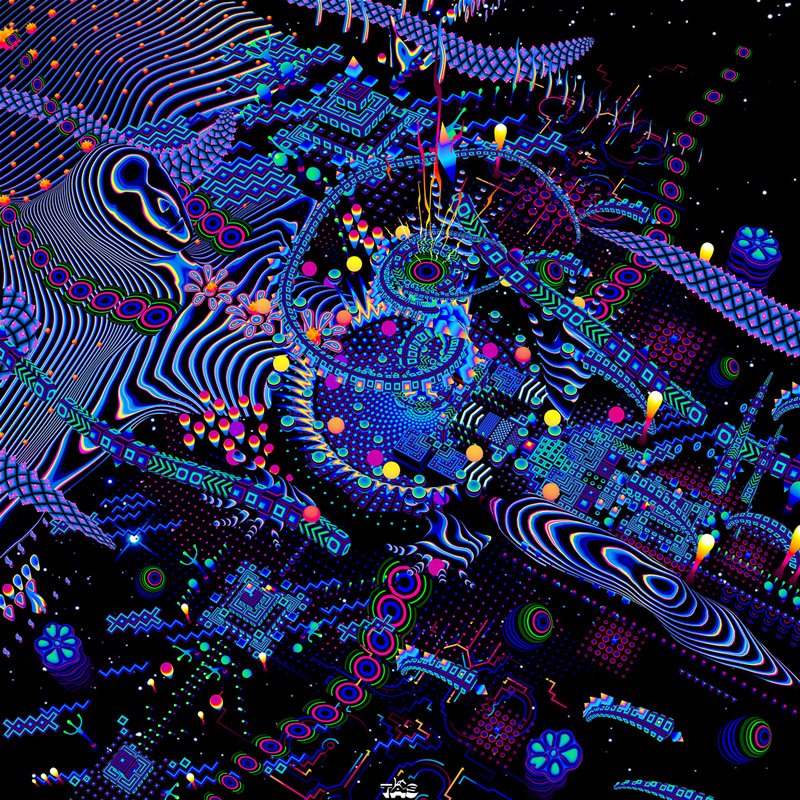

a gross representation of DMT space by TAS

The Psychoactive Bough